From Japan Dreams to Becoming a Chinese Translator

But that experience ended up changing how I saw language, work, and myself.

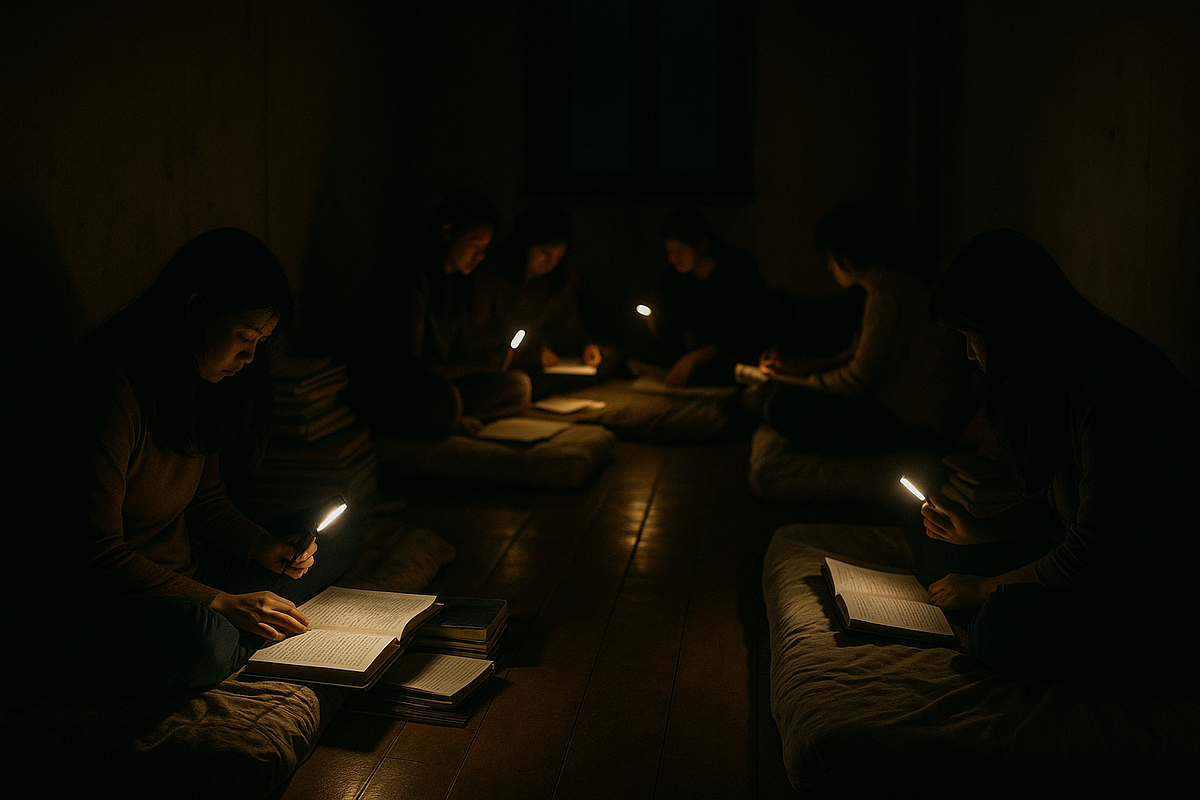

Sarah (fake name) sat beside me on the thin mattress we shared with three others, her voice barely above a whisper. She leaned close so no one else could hear.

“Can you read this for me? I think it’s about reporting our boss… but I’m scared.”

The glow from her small torch was our only light. It was past 10 p.m., and the sushi shop owner had just turned off the power to “save money.” Around us, girls lay on the floor, flipping through vocabulary books by flashlight. During the day, we made sushi rolls for $18 an hour in cash. At night, they studied English in hopes of a better life.

Sarah used to be a manager in Beijing. Now she lived in this cramped room, paying our boss for the privilege of sleeping on the floor. On paper, her job looked legal. In reality, she handed back most of her wages in exchange for a payslip that could extend her visa. After all the deductions, she was left with $4 an hour.

Some of the women were terrified of the idea of reporting the boss. They’d heard stories — that your visa could be cancelled, or you could be blacklisted in the industry. At least, they reasoned, this boss didn’t mind their poor English and was willing to provide a payslip for a visa extension. What if another restaurant wouldn’t give them even that chance? Sarah told me about a co-worker who had once tried to report her boss. Another colleague overheard, told the boss first out of fear for her own visa, and the whistle-blower was fired immediately. Opinions in the room were divided, and trust was fragile.

I was the best English speaker among them, so Sarah asked me to translate the Fair Work Ombudsman’s website. She wanted to know her rights but feared the consequences. As I explained her options, I realised something unsettling: without language, she had no way to defend herself — and without someone to bridge that gap, nothing would change.

I hadn’t planned to be here.

I graduated with a Bachelor in Business Administration, thinking a master’s degree in Japan would make me more competitive. But tuition wasn’t cheap, and Australia’s Working Holiday visa promised high wages. I thought I’d save money here, then head to Japan.

It took me three months to find my first job — a Chinese restaurant that paid $15 an hour in cash, off the books. I worked hard and was content, until I moved to a sushi shop for “better pay.” That’s when I saw the real cost: overcrowded staff housing, exploitative contracts, and co-workers trapped by language barriers and immigration rules.

Relying on my English skills, I quickly found a new, legal job in a laundry folding clothes for $24 an hour. I resigned from the sushi shop without ever receiving any pay. On my last day, Sarah came to see me off. She said she would study English harder so that one day she could work in a “white job” — a Chinese slang term for legal, on-the-books work — like mine, with payslips, proper wages, and dignity.

A few months later, Sarah told me she had gone through with the report. Fair Work officers investigated. The boss was fined, the workers were repaid, and her visa was extended — legally, this time.

She thanked me for my help. Without someone to translate for her, she said, it wouldn’t have been possible. She also discovered TIS National, Australia’s free government-funded interpreting service. That moment stayed with me.

I came to Australia chasing money for tuition. I left with something far more valuable: the realisation that language can change lives — including mine. That’s when I decided to learn a skill I could use anywhere, any day, to help people in ways that business theory never could.

If you’d told me back then that I’d become a translator between English and Chinese, I would’ve laughed. But I’ve seen how words can bridge gaps that money, power, and even good intentions cannot. And that’s a plan I’m proud to follow — wherever it takes me.